Delighting in God’s Instruction: Understanding Psalm 1 and the Law in Light of Yeshua

A defense case: Why Don’t Christians Follow the Law of Moses?

The Scriptures are a treasure trove of divine wisdom, revealing God’s heart and His plan for humanity. As someone shaped by Jewish tradition and ignited by faith in Yeshua (Jesus), I see these ancient texts as a unified story pointing to Him—the promised Messiah who fulfills the Hebrew Scriptures with breathtaking precision. In this exploration, we’ll dive into Psalm 1 and the idea of "delighting in the law of the Lord," tackling misconceptions about its meaning and its place in the lives of Christians today. Using sound logic, trusted hermeneutical principles, and insights from Jewish tradition, we’ll uncover how these verses illuminate Yeshua as the culmination of God’s redemptive purpose.

This journey is for everyone—whether you’re a seasoned student of Scripture or just beginning to explore. My goal is to balance intellectual depth with an accessible, engaging tone, offering clarity without losing the wonder of God’s Word. Let’s embark on this together, with open hearts and curious minds, to see how the old and new weave into one magnificent tapestry of truth.

Psalm 1: Delighting in God’s Torah

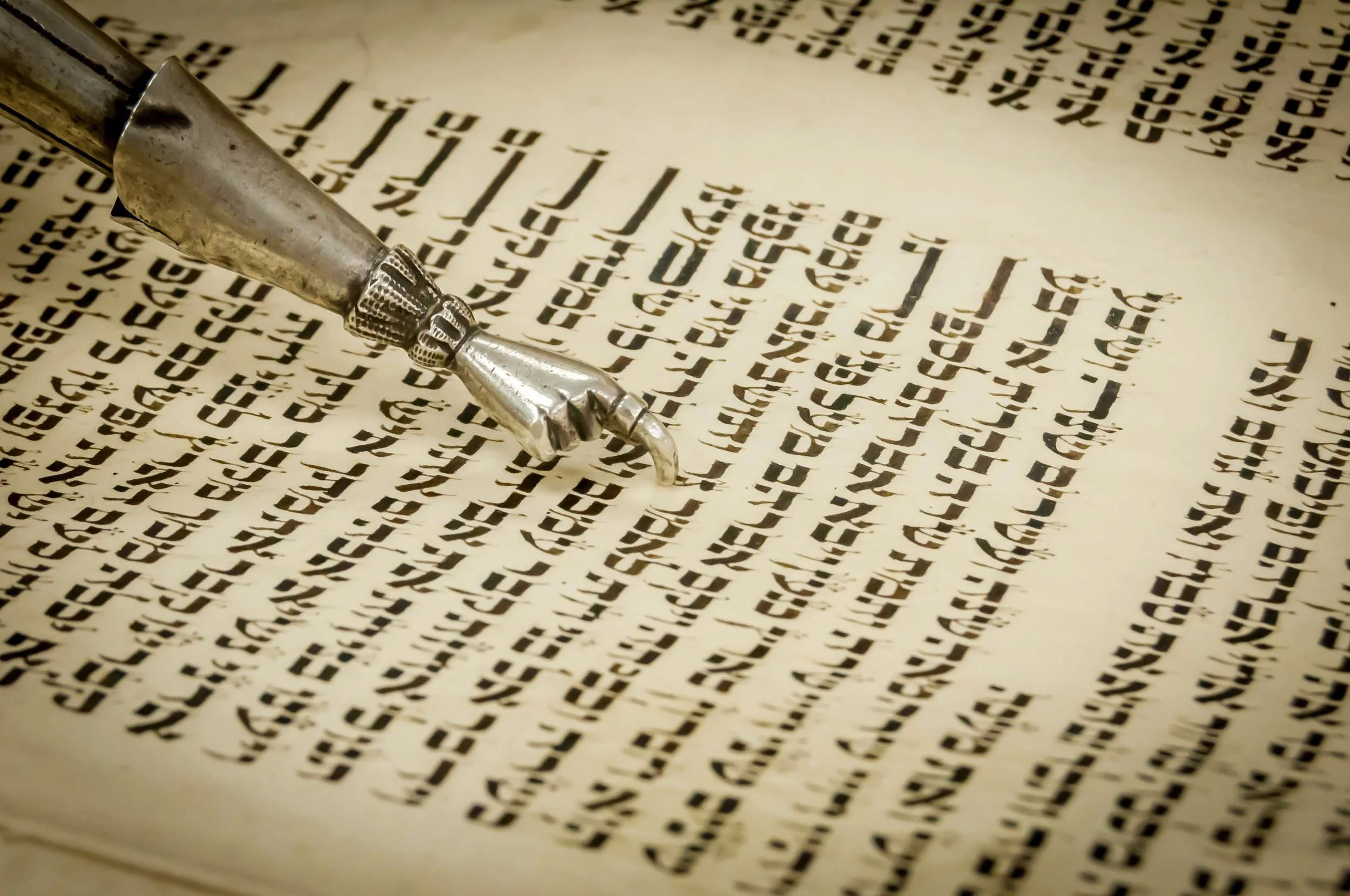

Psalm 1 sets the stage with a vivid contrast between the righteous and the wicked. Verse 2 describes the blessed person: "But his delight is in the law of the Lord, and on his law he meditates day and night." At first glance, "law" might bring to mind rules or regulations—like speed limits or tax codes. But the Hebrew word here, torah (תּוֹרָה), tells a richer story.

Derived from the root yarah (יָרָה), meaning "to teach" or "to instruct," torah isn’t just a legal code. It’s God’s teaching, His guidance, His wisdom—encompassing the Pentateuch (Genesis to Deuteronomy) with its narratives, commandments, and revelations of divine character. The word "delights," chaphets (חָפֵץ), means "to take pleasure in" or "to desire." So, the blessed person in Psalm 1 finds joy in God’s holistic instruction—not merely in following rules.

Picture a painter who delights in studying color theory. It’s not about rigid obligation; it’s about how understanding deepens their love for the craft. Similarly, delighting in torah is about savoring God’s ways—His justice, mercy, and truth. Comparing this to civil laws misses the mark. Civil codes are external enforcements; torah is relational, covenantal, and tied to God’s very nature. It’s less about compliance and more about communion with the One who instructs us for our flourishing.

How does this connect to Yeshua? As the living Word (John 1:1), He embodies torah—God’s teaching made flesh. Delighting in torah foreshadows delighting in Him, the One who perfectly reveals God’s wisdom and will.

Christians and the Law of Moses

For Christians, especially Gentile believers, the relationship with the Law of Moses—think circumcision, dietary laws, or Sabbath observance—can feel confusing. Historically, this law, given at Sinai (Exodus 19–20), was a covenant between God and Israel. Obedience, or shama (שָׁמַע)—meaning "to hear" or "to obey"—was about trusting God’s voice within this relationship. Gentiles weren’t part of this covenant unless they joined Israel (Exodus 12:48).

In the New Testament, Paul uses the Greek word nomos (νόμος) for "law," teaching that believers are not "under the law" (upo nomon, ὑπὸ νόμον) but "under grace" (upo charin, ὑπὸ χάριν) (Romans 6:14). "Under the law" refers to facing its condemnation for sin; grace lifts that burden. But does this mean the law disappears? Not at all.

Jesus addresses this directly in Matthew 5:17: "Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them." For Gentile readers, "fulfill" might sound like finishing a task and moving on, but the Greek word here, pleroo (πληρόω, pronounced plā-ROH-oh), means "to fill up," "to complete," or "to bring to full expression." It’s not kataluo (καταλύω), which means "to destroy" or "abolish." Jesus isn’t scrapping the law; He’s revealing its true purpose.

Think of a musician playing a score. They don’t toss out the notes—they bring them to life through performance. That’s what Jesus does with the law. He lived it perfectly, showing its heart. For instance, He taught that "do not murder" isn’t just about the act—it’s about not even harboring anger (Matthew 5:21–22). Fulfilling the law means embodying its deepest intent—love, justice, mercy—not just following rules outwardly.

So, what does this mean for Gentile believers? You’re not under the Mosaic covenant’s ceremonial aspects—like sacrifices or dietary laws (Acts 15 confirms this). But the moral principles Jesus lived out—like loving God and neighbor—still guide Christian life. He didn’t end the law’s value; He transformed it. Through His life and Spirit, Christians can live its ethical core—not as a burden, but as a response to grace. The law isn’t abolished; it’s fulfilled in Christ, who shows us how to live it and empowers us to do so.

The Jerusalem Council in Acts 15 reflects this balance. Gentile believers weren’t required to adopt all Jewish practices (like circumcision), but they were to uphold moral standards (e.g., avoiding idolatry). The law’s ethical core persists, reshaped by Yeshua’s work. In Hebrew tradition, shama was about relational trust, not flawless perfection—Israel stumbled in faith, not because the law was impossible.

Yeshua fulfills the Mosaic Law by embodying its purpose—righteousness and relationship with God—offering Himself as the ultimate sacrifice and mediator of a new covenant (Hebrews 8:6). Christians aren’t "bound" in the old covenant sense, but the law’s principles live on, reshaped by grace.

The Torah: Gift or Burden?

To fully grasp the law’s role, let’s explore how the Torah is understood in Jewish tradition—not as a burden, but as a profound gift from God.

In Jewish thought, the Torah is far more than a set of rules; it’s a divine revelation encompassing laws, moral teachings, ethical principles, and spiritual guidance. Derived from yarah (יָרָה), "to teach," Torah reflects God’s instruction for living a holy, meaningful life. Far from a heavy yoke, it’s celebrated as a precious gift—a blueprint for flourishing in relationship with God and others. This aligns with Psalm 1:2, where the blessed person "delights" (chaphets, חָפֵץ) in the Torah, finding joy in meditating on it day and night.

Jews see the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai (Exodus 19–20) as an act of divine grace, when God revealed His will and drew humanity into covenant. The commandments, or mitzvot (מִצְווֹת), are not burdensome obligations but opportunities to sanctify life—acts of worship connecting the individual to the Divine. Historically, the Torah wasn’t a means to earn salvation; it was given to a people already redeemed from Egypt (Exodus 14–15), as a way to live out their identity as God’s chosen nation. Abraham’s faith, credited as righteousness (Genesis 15:6), shows salvation has always been by grace.

While the Torah reveals sin and humanity’s need for redemption (Romans 7:7), this too is its gift, pointing to the Messiah who fulfills its purpose. In Jewish tradition, it’s approached with reverence and joy—a source of wisdom reflecting God’s character.

Some Christian views contrast this, seeing the law as a burden—a temporary guardian highlighting sin until faith in Jesus (Galatians 3:23–25). This emphasizes freedom from condemnation, with salvation by grace, not works. Yet, this can obscure the law’s enduring value. Others see the Torah as reflecting God’s unchanging nature, offering timeless ethical guidance, even if not the path to righteousness.

Yeshua bridges these perspectives: "Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them" (Matthew 5:17). Pleroo (πληρόω), "to fulfill," suggests completion. Yeshua embodied the Torah perfectly, revealing its intent through His life and teachings. His sacrifice offers a new engagement with the Torah—not to earn favor, but as a response to grace. For His followers, it becomes a guide for living God’s will, empowered by the Holy Spirit.

Thus, the Torah is neither a crushing burden nor an outdated relic. In Jewish eyes, it’s a gift of grace and wisdom; through Yeshua, it finds fulfillment, uniting Hebrew Scriptures and the New Testament in a redemptive narrative.

The Moral Law and the Ten Commandments

In Hebrew, the Ten Commandments are called aseret hadevarim (עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים), "ten words," emphasizing divine speech over legalism (Exodus 20). These aren’t arbitrary rules; they mirror God’s nature—His holiness, justice, and love. For Israel, obedience (shama) was covenantal, not optional.

Jesus reaffirms their essence in Matthew 22:37–40, distilling them into love for God and neighbor. Paul echoes this: "Love is the fulfilling of the law" (Romans 13:10). The New Testament doesn’t discard them; it reorients them through agape (ἀγάπη), sacrificial love.

The distinction between "moral" and other laws (ceremonial or civil) is a later theological lens, not explicit in Scripture. Torah and nomos are a unified whole—ceremonial, civil, and moral aspects interwoven. Saying Christians aren’t "required" to follow the Ten Commandments can mislead. Obedience (hupakouo, ὑπακούω, "to submit") isn’t a legal yoke but a grace-filled response. Yeshua upholds these "words" as timeless, fulfilled in His life and call to love.

The Law of Christ

The "Law of Christ" (nomos Christou, νόμος Χριστοῦ) appears in Galatians 6:2—"Bear one another’s burdens, and so fulfill the law of Christ"—and 1 Corinthians 9:21. It’s about love, modeled after Yeshua’s example (John 13:34–35). Grace (charis, χάρις) forgives, but Paul rejects lawlessness: "Shall we sin because we are not under law but under grace? By no means!" (Romans 6:1–2).

Is it "harder" than the Mosaic Law? Not exactly. The Hebrew torah already targeted the heart (Deuteronomy 6:6), and Yeshua deepens this (Matthew 5:21–28). The prophets foretold a law written on hearts (Jeremiah 31:33), which the New Covenant fulfills. The "Law of Christ" isn’t a tougher rulebook; it’s an internal transformation—obedience flowing from love, not obligation.

Yeshua embodies this law, living it perfectly and empowering us through His Spirit. It’s not about increased difficulty but a higher calling to reflect God’s character, made possible by grace.

Historical Misconceptions and the Modern Church

The church’s understanding of the law—God’s torah or instruction—has been shaped by historical developments, theological traditions, and translation choices. While these have enriched Christian thought, they’ve also introduced misconceptions that persist today, often clouding the law’s true purpose and beauty as depicted in Psalm 1. Let’s examine three key examples: the King James translation, Roman Catholic logic, and Reformed theology, and see how they influence modern perceptions.

1. The King James Version: Translation and Its Lasting Echoes

The King James Version (KJV), published in 1611, is a cornerstone of English-speaking Christianity. Its poetic language has inspired generations, but its rendering of the law reflects the era’s assumptions, sometimes leading to misunderstandings.

The Hebrew torah, meaning "teaching" or "instruction," is consistently translated as "law" in the KJV. In Psalm 1:2, we read: "But his delight is in the law of the Lord; and in his law doth he meditate day and night." While technically correct, "law" in English suggests a legalistic framework—rules and penalties—rather than the broader, life-giving guidance torah conveys. This shift can make the law seem more about obligation than delight.

In the New Testament, the KJV’s use of "law" for nomos (νόμος) can further confuse. Paul’s discussions (e.g., Romans 7:23, "the law of sin") span various meanings, from the Mosaic covenant to moral principles. Without distinction, readers might view the law as a uniform burden rather than a multifaceted gift.

Modern Impact: The KJV’s enduring popularity means many Christians encounter Scripture through its lens. Its majestic tone can discourage deeper inquiry into original meanings, fostering a view of the law as outdated rules. This assumption—that "law" fully captures torah—persists, distancing believers from its joy.

2. Roman Catholic Logic: Tradition and the Balance of Grace

Roman Catholic theology has approached the law through tradition and the magisterium, the church’s teaching authority. This perspective, especially during the Reformation, shaped a unique view of the law’s role.

Catholic doctrine upholds the law’s relevance, particularly the "moral law" (e.g., the Ten Commandments), as a guide. The Catechism of the Catholic Church calls it "a pedagogy and a prophecy of things to come" (CCC 1964), pointing to Christ. However, the medieval focus on penance and works sometimes implied that adherence to the law and church practices could merit grace, prompting the Protestant Reformation’s emphasis on faith alone (sola fide).

This tension suggests a potential misstep: the idea that human effort could achieve righteousness. While Catholic theology affirms grace, its historical emphasis on works could obscure the law’s role as a revealer of sin and a signpost to the Savior.

Modern Impact: The Reformation’s reaction led many Protestant churches to downplay the law, fearing legalism. This creates a false dichotomy—law versus grace—rather than a holistic view where the law complements grace. Today, some dismiss the law as irrelevant, missing its ethical depth.

3. Reformed Theology: Sovereignty and the Risk of Rigidity

Reformed theology, from the Protestant Reformation and figures like John Calvin, emphasizes God’s sovereignty and human depravity. Its approach to the law is insightful but can foster a negative slant.

Calvin outlined three uses of the law:

Pedagogical: It reveals sin, showing our need for grace.

Civil: It restrains evil in society.

Normative: It guides believers in holy living.

This acknowledges the law’s value under the New Covenant. However, the focus on human inability and the law’s condemning power (e.g., Romans 3:20) can overshadow its positive role. In Psalm 1, the righteous delight in the law, yet an overemphasis on its role as a "schoolmaster" (Galatians 3:24, KJV) might cast it as a harsh judge rather than a gracious gift.

Modern Impact: This stress on the law’s diagnostic role can foster a view of it as a tool of conviction rather than sanctification. Some modern churches caricature the law as an enemy of grace, missing its partnership in God’s plan and its invitation to delight.

The Modern Church: Cultural Traps and Lost Contexts

Beyond these influences, cultural pressures and a disconnect from biblical roots compound misconceptions. In an era of quick answers, phrases like "We’re not under law, but under grace" (Romans 6:14) are stripped of nuance, implying the law’s irrelevance. This ignores how grace fulfills its purpose.

The church’s drift from its Jewish foundations—lacking Hebrew context or covenantal understanding—further obscures the law’s intent. The result? A shallow view where the law is either a relic or a yoke, not a pathway to delight.

Yeshua: Reclaiming the Law’s True Purpose

These misconceptions stem from missing Yeshua’s fulfillment. He said, "Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them" (Matthew 5:17). He embodied the law’s intent, revealing it as a guide to God’s character and our need for redemption.

By returning to torah as instruction, nomos in its varied senses, and Jewish views of the law as a gift, we can move past fallacies. The law isn’t discarded or burdensome; it’s fully realized in Yeshua, the Word made flesh.

The Fulfillment in Yeshua

From Psalm 1 to the Law of Christ, Scripture tells a consistent story. Delighting in torah—God’s teaching—points to Yeshua, the Word incarnate who fulfills its every promise. The Law of Moses finds its climax in His righteousness, the Ten Commandments their echo in His love, and the Law of Christ its heartbeat in His sacrifice. This isn’t abolition but completion, not burden but beauty.

Objections might arise: "If Jesus fulfilled the law, why care about it?" Because it reveals God’s unchanging nature, guiding us to Him. "Isn’t this just for Jews?" No—through Yeshua, all nations join God’s covenant (Isaiah 49:6, Acts 10:34–35). The evidence is clear: the Hebrew Scriptures pulse with messianic hope, met in Yeshua’s life, death, and resurrection.

I invite you to explore this yourself. Open the Scriptures—start with Psalm 1, Matthew 5, or Romans 13—and trace the thread. Reflect on how Yeshua transforms these ancient words into living truth. What do you see? Share your thoughts below, and let’s journey deeper together. May this spark a passion to know Him more—the Messiah who bridges the old and new with grace and glory.